Front cover illustration:

Sylvia Plath’s writing room at Court Green,

in North Tawton, Devon, U.K.

Rooms of Their Own

Where Great Writers Write

Alex Johnson

Illustrations by James Oses

192 pages, Hard Cover

Published by Frances Lincoln

By Quill 🪶 ‘n’ Ink Pot

This fascinating book, well bound and smelling candidly chemical, a gift from a loved one, reached me in a beautiful flower and nature print covered box, by special delivery all the way from Australia.

A brand new book, recently published in 2022, of which the contents span from Honore de Balzac (1799-1850), right down to J. K. Rowling (1965-), with everything about the spaces they and other selected writers created for themselves to write in, into the types of ink and pencils they wrote with.

Something that struck me while reading half way through the book was that writers seemed to come across as being financially well endowed. I’m thinking this in comparison to let’s say artists and painters who for the most part created through meagre existences. Writers had the money to sometimes have their writing spaces placed in two or three different locations even across the high seas. Then, there was Edith Wharton who “designed her forty-two-room mansion the Mount in Lenox, Massachusetts, [USA], and put her bedroom and sitting room suite above the library to make sure it was quiet when she was working.”

The writers picked by Alex Johnson for this glorious collection, come from varied places on the planet. Haruki Murakami from Tokyo, Japan, to Anton Chekhov, forty miles south of Moscow, in Russia, who actually wrote in Russian. Most of them are from the British Isles and the United States of America. This is quite understandable as the writer is focusing mainly on writers writing in the English language and not on authors whose work have been translated into English.

Only a few authors in translation are featured here to my knowledge. Due to this reason perhaps, the latin writers such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and the French, Jean Paul Satre, are missing from the Contents. Although Satre is mentioned in the book in relation to featured writers. So are Flaubert, Jorge Luis Borgese and Tolstoy, missing, for example. I found that Johnson had also very carefully avoided adding writers of controversy with political or moral concerns to his collection. Those of such bent that I found prominently omitted are Salman Rushdie, Pablo Neruda, who is mentioned, and Vladimir Nabakov who is also mentioned

Argentine writer and poet, Jorge Luis Borges, whom I may add, having created the hypertext in his story, Garden of Forking Paths, directly linking it with the hyperlink now used in computer searches, in my belief needing a place in the book, even though he wrote in Spanish. Having said this, I believe what Johnson has aimed at is to give the reader a well rounded mix of the genres of writing chosen by the authors he has picked, and not to give us as numerous a number of writers, as such. This is a very clever idea indeed and speaks much for Johnson’s ability to sift through all the many authors available to us at our disposal, and find the right ones for what he wants to convey.

Shakespeare and other poets and playwrights of the Elizabethan age and those of the 13th to 17th Centuries are only mentioned with reference to other writers. This is possibly due to not much information on their spaces and habits being available to us today.

This richly illustrated book consists of thick paper and comes replete with a table of Contents, beautiful watercolour illustrations by James Oses, Visitor Information, should you choose to make this journey yourself in reality, an Index, should you choose to use the book as a reference point for research, and Picture Credits.

The scope of the book is limited to the spaces occupied while writing by the great writers with no insertions such as samples of their writing. In doing so Johnson has made it an easy and enjoyable read. Research into original manuscripts and quoting from the works are deliberately avoided. He has deterred from being erudite and scholarly which is astute when presenting a book of this nature, which can be read for pleasure with its many illustrations, as well as for the purpose of study, without being too arduous.

We are told about how writers wrote, on what types of paper with what types and shapes of pencils, the typewriters they used and the types of ink they used when writing their work. In one instance even the material used in the preparation of their own ink is noted. Most of the earlier writers wrote with the help of quills, spilling ink as they went about their “work”. The hours and times of the day they chose to write are also revealed to us with some of them rigorously writing into thousands of words in a given morning. It truly is work indeed.

The spaces that they wrote in are as fastidious as they come. From George Bernard Shaw (1856-1920), who’s “writing refuge was a 65sq ft (6 [square metre]) wooden summerhouse, originally intended for his wife Charlotte and inspired by the similar set-up owned by his neighbour, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the naturalist who was part of [Robert Falcon] Scott’s expedition to the Antarctic. The hut at his home in Shaw’s Corner, Ayot St. Lawrence, Hertfordshire…, [I believe that’s where, “Hertford, Hereford and Hampshire/ Hurricanes hardly ever happen”*, came from], … was built on a revolving base that used castors on a circular track. This meant that it could be rotated to improve the light or change the view (or indeed just for a bit of exercise).”

Many of them writing in seclusion from hotel rooms. Others choosing the distractions that cafes provide. Some others write from their beds and quite a number of them opting for the ubiquitous writing table or writing desk, in the quiet solitary confines of a study or the parlour as in the case of Jane Austen.

Although Jane Austen herself is not among my own favourite authors. I remember well having studied Emma, at school, in literature class.

Others preferred the more salubrious settings of the Lake District, where William Wordsworth (1770-1850), wrote from. “William and, [is sister], Dorothy set about building their very own version.” … of a building they came across on a tour of Scotland in 1803, which she described as a ‘hay-stack scooped out’. “It was a simple circular, domed wooden hut, lined with moss,” Which goes to show what an important part writing spaces played in the very writing of the work itself.

“By the autumn of 1804, the new hut was in place, at the top of their garden, and higher than the cottage. While Wordsworth wrote in most of the rooms of his home, this was where he was happiest working. It was lined with moss and covered outside with heather, with a long seat around the interior. William likened it to a wren’s nest, facing west for the afternoon sun …. The working conditions were certainly inspirational as it was during this time that he wrote some of his most famous poems, including The Prelude and ‘I Wondered Lonely as a Cloud’.”

The book also gives us insights into how these spaces were preserved for posterity for the most part as treasured spaces of museumal value or replicated in other instances in different places.

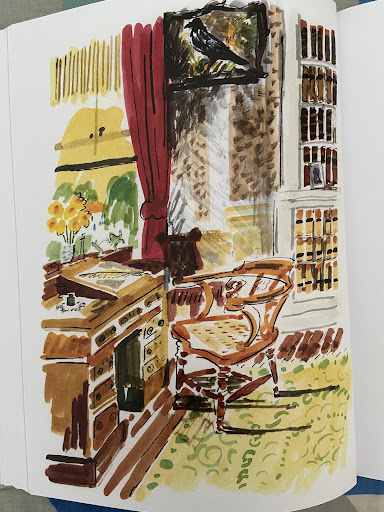

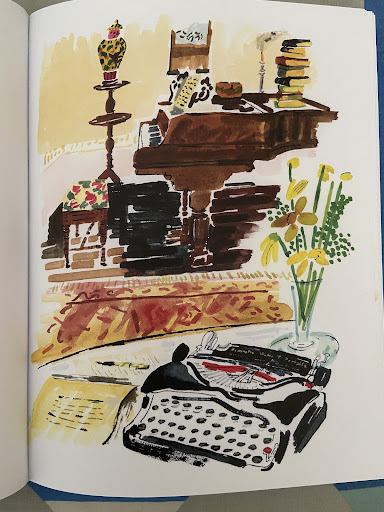

Here is an illustration from the Book, of Charles Dickens’s writing spaces:

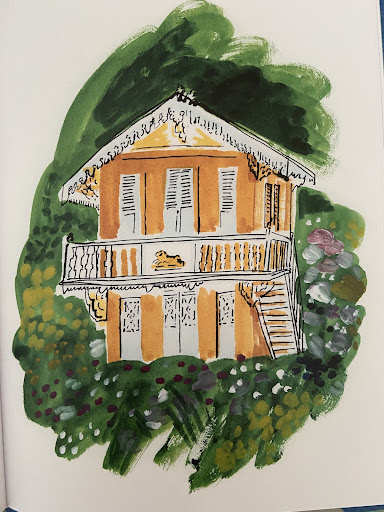

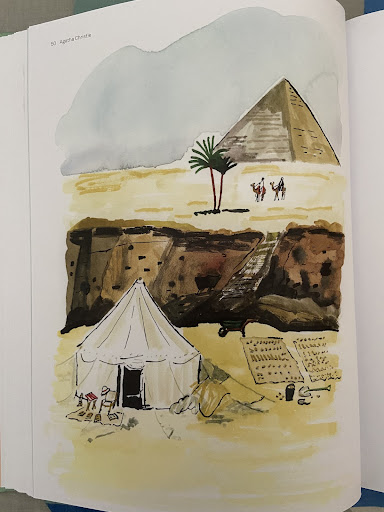

This is Agatha Christie’s favourite way to write in illustration:

Illustrations by James Oses

It is noteworthy that some of the writers were themselves designers as well as decorators, like Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, John Steinbeck and Edith Wharton were, and garden designers like Vita Sackville-West. The first building she restored being the tall tower of the “largely dilapidated sixteenth-century Sissinghurst Castle in Kent”, to which she moved with her husband Sir Harold Nicolson in 1930.

Roald Dahl’s (1916-90), space which “He called … his ‘little nest’ and the layout has a feeling of a home-made cockpit … decorated with many reminders of his time as a pilot …”, “the hut was built by Dahl’s friend, a local builder called Wally Saunders (later the inspiration for the BFG), and every last part – including the dust – moved into the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre in 2012. https://www.roalddahlmuseum.org/ not www.roalddahlmuseum.com as appears in the Visitor Information.

“Inside is an old Parker Knoll armchair where Dahl sat, writing on a green baize-covered wooden board balanced across its arms. Everywhere there is the flotsam and jetsam of life, from his own hipbone to the ashtray filled with his wastepaper bin.”

Dahl being one of my favourite of all writers. “,,, Dahl’s Gipsy House home in Buckinghamshire; a photo of him hugging Sophie; [his granddaughter], a rock veined with opal sent to him by a young boy fan in Australia; and a pinecone, a reminder of his happy childhood holidays in Norway.”

Apparently, Dylan Thomas’s shed “motivated Roald Dahl to build his own writing hut to exactly the same proportions, (see page 54) following a family trip to Wales, …”

Rejection by publishers was very much a part of the lives of writers as portrayed here:

Visitor Information. p.186

“Many of the locations described in this book are private, and cannot be visited.”

These detailed bits of information on how to access the writers’ writing spaces in a real life expedition is made possible to those who are interested in and inclined towards making this, part of their travels. The journey that you were taken through in the 185 pages of this book culminates in the Visitor Information. A journey well worth continuing and been undertaken in your very own travels.

Lo and behold, I find this amazing piece of information on Vita Sackerville-West:

Minerva Press being where I was first published. All I can say is, the world is indeed a small place.

I shared the link to this post to our Instagram account since logged out from, for speaking out the Truth. What I want to share here is that the writer, Alex Johnson made the following comment over there, which I fortunately saved, and here it is:

* words from the 1964 film My Fair Lady based on George Bernard Shaw‘s stage play Pygmalion