In the Spotlight

By Joseph M. Hanneman December 8, 2022 Updated: December 9, 2022

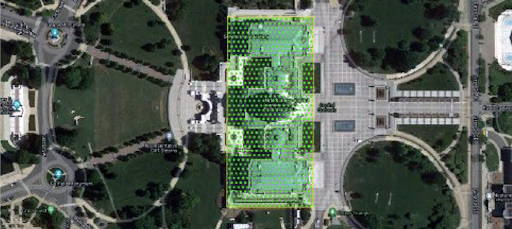

The FBI’s “alarming” use of general warrants to scoop up the private location data of the devices of thousands of people on Jan. 6, 2021, was a violation of the Fourth Amendment that enabled an illegal four-acre dragnet to generate criminal charges without probable cause, defense attorneys argue in federal court filings.

In the wake of the protests and violence at the U.S. Capitol, the FBI served search warrants on technology giant Google Inc. and telecommunication companies, including AT&T.

The warrants sought to determine who was in and around the Capitol during the hours of unrest and rioting, court filings indicate.

Unlike other common uses of search warrants—served against specific individuals or for specified things—general warrants seek the identity of potential defendants first, with the alleged crimes coming later, defense attorneys say.

“The geofence warrant requested and authorized here collected an alarming breadth of personal data,” wrote attorney Rebecca Fish, an assistant public defender who represents Jan. 6 defendant David Charles Rhine, 53, of Bremerton, Washington.

Fish asked U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras to suppress location-history evidence, “as well as the fruits of that evidence, obtained by a modern-day general warrant in violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

In order to identify Google users who might have been in or near the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, Google had to run a query of all account holders who had enabled the location-history feature—“numerous tens of millions” of people—Fish wrote in a motion to suppress the so-called geofence warrants.

Google had to “search across all [location history] journal entries to identify users with potentially responsive data and then run a computation against every set of coordinates to determine which records match the time and space parameters in the warrant,” Fish wrote.

Based on Google figures, Fish said the location-history search had to be run against more than 500 million user accounts. This yielded a list of “5,723 unique devices that Google estimated were or could have been in the geofence during the four-and-a-half-hour period requested,” she wrote.

If a user has location history enabled, then Google estimates the device’s location using GPS satellites, nearby WiFi networks, Bluetooth beacons, and cell towers. It records the location as often as every two minutes, even if the phone is not in use, the motion said.

The Google estimates have several major issues regarding accuracy and specificity, Fish’s motion contends.

The location radius shown on Google’s maps has an error rate such that “there is up to a 32% chance that the user in any of this data is actually not within the radius surrounding the estimated location and could be somewhere else,” the motion said.

Rhine was arrested in November 2021 and charged with four federal crimes: entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds, disorderly and disruptive conduct in a restricted building or grounds, disorderly conduct in a Capitol building, and parading, demonstrating, or picketing in a Capitol building.

Rhine is one of some 950 people arrested and charged with crimes for being at the Capitol on Jan. 6. Geolocation data was used extensively to help identify people who were at the Capitol protests.

Although Google’s “location history” feature requires the user to opt in, it’s unclear what percentage of Google users are aware that their phones or other devices could be used for surveillance purposes by law enforcement.

A Chilling Effect?

Use of dragnet warrants will likely have at least one major side effect: the chilling of First Amendment-protected speech, according to Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch.

“This is a huge area of land around the Capitol that is typically accessible to the public,” Fitton told The Epoch Times, “as many of those thousands were there in unknowing violation of the rules, exercising their First Amendment rights.”

Fitton said the investigations seem to go beyond people suspected of violence or other criminal activity at the Capitol.

“The group of individuals I think they’d be interested in are those who entered the building or engaged in violence,” Fitton said. “And how does this warrant get them to that spot? Well, you know what it does, it gets them to be at the spot of, ‘let’s scare folks from participating in other First Amendment-protected activities in the future.”

Law enforcement requests for Google location data “have become increasingly common in recent years,” Google wrote in an amicus curiae brief in the 2019 case United States v. Chatrie.

Google asked the judge in that case to hold that both the federal Stored Communications Act and the Fourth Amendment “require the government to obtain a warrant supported by probable cause to obtain [location history] information stored by Google users.”

In the Rhine case, the FBI warrants “sought identifying information for any device for which Google was 68 percent confident the device was somewhere within the geofence at a single moment during the four-and-a-half-hour geofence period,” Fish wrote. “Again, the government equated presence to criminality.”

The FBI also sought Google subscriber information for any device for which the location history was allegedly deleted between Jan. 6 and Jan. 13, “and had at least one data point where even part of the display radius was within the geofence,” Fish wrote.

An FBI agent said criminals tend to delete their Google location history “to protect themselves from law enforcement,” the motion said.

Prosecutors said Rhine failed to show his Fourth Amendment rights were violated by the search warrants.

‘Ample Independent Evidence’

“Second, even if the defendant could show a Fourth Amendment violation, the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule would preclude suppression,” wrote Department of Justice attorney Francesco Valenti. “Third, and at a minimum, any defect in the geofence warrant would not invalidate the subsequently obtained warrant to search the defendant and his electronic devices, which was supported by ample independent evidence.”

Attorneys in another Jan. 6 case—United States v. Lloyd Casimiro Cruz Jr.—are also seeking to suppress cell phone location data because the search warrant used to obtain it “was fruit of the poisonous tree, and thus this case must be dismissed.”

Cruz, 40, of Polo, Missouri, was arrested in February 2022 and charged with entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds, and parading, demonstrating, or picketing in a Capitol building.

“The entire complaint against the defendant originated with an unlawful blanket general warrant of cell phone location data, which plainly lacked requisite specificity,” attorney John Pierce wrote in a motion to suppress. “Investigators then used such metadata to identify Cruz, rather than first having probable cause to identify Cruz and probable cause to believe Mr. Cruz had committed an offense as required by the 4th Amendment.”

Pierce described the investigation as using “one of the worst general warrants in American history.” He asked U.S. District Judge Reggie Walton “to open a more wide-ranging inquiry into the FBI’s use of these unconstitutional warrants.”

“The warrants in this case plainly lacked probable cause with any particularity regarding the persons and things to be searched or even the crimes to be alleged,” Pierce wrote.

Federal prosecutors said Cruz had no expectation of privacy inside the Capitol building or within the device-location data kept by Google and AT&T.

“The government obtained search warrants that were supported by probable cause and that specified their objects with particularity,” wrote Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Tessman. “These were not impermissible ‘general warrants.’ Finally, suppression would be inappropriate in all respects because investigators relied on the warrants in good faith.”

Fitton said the process being used has it backward.

“Some of the law enforcement approach is, ‘we’re going to figure out who was there and then work to kind of rule people out,’” Fitton said. “Well, no, that’s not the way it necessarily works because you’re not subjected to having your material vacuumed up by the government just because you happen to be in that area. That’s not appropriate.”

Joseph M. Hanneman

Joseph M. Hanneman is a reporter for The Epoch Times with a focus on the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol incursion and its aftermath; and general news in the State of Wisconsin. His work over a nearly 40-year career has appeared in Catholic World Report, the Racine Journal Times, the Wisconsin State Journal and the Chicago Tribune. Reach him at: joseph.hanneman@epochtimes.us