JERUSALEM, PLATE 35, ‘THEN THE DIVINE HAND….’, PRINT MADE BY WILLIAM BLAKE, 1757–1827, BRITISH, 1804 TO 1820, RELIEF ETCHING PRINTED IN ORANGE WITH PEN AND BLACK INK AND WATERCOLOUR ON MODERATELY THICK, SMOOTH, CREAM WOVE PAPER, SHEET: 13 1/2 X 10 3/8 INCHES (34.3 X 26.4 CM) AND PLATE: 8 7/8 X 6 1/2 INCHES (22.5 X 16.5 CM), DIVINE, FIRE, FLAMES, HAND, JERUSALEM, LITERARY THEME, MEN, NUDES, RELIGIOUS AND MYTHOLOGICAL SUBJECT, TEXT, WOMEN

| ‘Jerusalem’ And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England’s mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England’s pleasant pastures seen? And did the Countenance Divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among these dark Satanic mills? Bring me my Bow of burning gold: Bring me my Arrows of Desire: Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold! Bring me my Chariot of fire. I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England’s green and pleasant Land. William Blake From Milton, Preface |

From Wikipedia –

“And did those feet in ancient time” is a poem by William Blake from the preface to his epic Milton: A Poem in Two Books, one of a collection of writings known as the Prophetic Books. The date of 1804 on the title page is probably when the plates were begun, but the poem was printed c. 1808.[1] Today it is best known as the hymn “Jerusalem“, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry in 1916. The famous orchestration was written by Sir Edward Elgar. It is not to be confused with another poem, much longer and larger in scope and also by Blake, called Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion.

It is often assumed that the poem was inspired by the apocryphal story that a young Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, a tin merchant, travelled to what is now England and visited Glastonbury during his unknown years.[2] Most scholars reject the historical authenticity of this story out of hand, and according to British folklore scholar A. W. Smith, “there was little reason to believe that an oral tradition concerning a visit made by Jesus to Britain existed before the early part of the twentieth century”.[3] Blake does not name the walker on “England’s green and pleasant land”; according to a story available at the time of Blake’s writing, in Milton’s History of Britain, Joseph of Arimathea, alone, travelled after the death of Jesus, and first preached to the ancient Britons.[4] The poem’s theme is linked to the Book of Revelation (3:12 and 21:2) describing a Second Coming, wherein Jesus establishes a New Jerusalem. Churches in general, and the Church of England in particular, have long used Jerusalem as a metaphor for Heaven, a place of universal love and peace.[a]

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake asks whether a visit by Jesus briefly created heaven in England, in contrast to the “dark Satanic Mills” of the Industrial Revolution. Blake’s poem asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ’s visit.[5][6] The second verse is interpreted as an exhortation to create an ideal society in England, whether or not there was a divine visit.[7][8]

Cover to his Complete Works

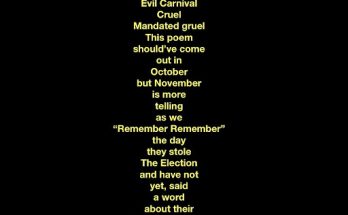

Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant- ‘Then the Divine Hand’ showing Christ soaring above Albion within whose bosom ‘the Divine hand found the Two Limits, Satan and Adam’, 1804

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. What he called his “prophetic works” were said by 20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”.[2] His visual artistry led 21st-century critic Jonathan Jones to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”.[3] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC’s poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[4] While he lived in London his entire life, except for three years spent in Felpham,[5] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich collection of works, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”[6] or “human existence itself”.[7]

– Wikipedia