This article was first published in The New York Times. I was compelled to post it in full here, as the newspaper kept asking you to pay for reading this in its former form, posted in Leaf Blogazine dated March 13, 2018 !!!

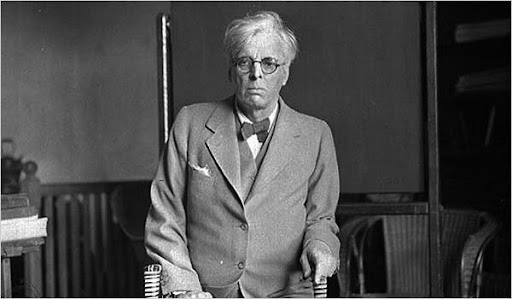

William Butler Yeats in an undated photo.

Credit…

Courtesy of The National Library of Ireland

By Jim Dwyer

- July 20, 2008

DUBLIN

SO here, under airtight, light-shielding glass, is a notebook given to William Butler Yeats in 1908 by Maud Gonne, the beautiful, brainy feminist Irish revolutionary and object of Yeats’s infatuation across five decades, the muse well, really, the furnace for his poetry of yearning and his willing partner in what they called a mystical marriage. As far as actual marriage, Gonne became expert at wielding the word “no.”

Bound in white vellum, the notebook served as their metaphysical marital bed. Yeats used it to keep track of their shared fixation with the occult and each other. One morning in July 1908 Gonne wrote from Paris to report that she had been seized by a vision. “I had such a wonderful experience last night that I must know at once if it affected you & how?” she wrote. “At a quarter of 11 last night I put on this body & thought strongly of you & desired to go to you.”

Yeats taped the letter into the notebook. Now, a century later, that book is on display at the National Library of Ireland, opened to a page that is just barely visible under the indirect lighting prescribed for aged ink treasures. Yet every syllable every comma-deprived sentence, every curve in her script, every ampersand is legible. Next to the display case the entire notebook has been digitally reincarnated. With the stroke of a finger on a touch screen, a visitor can flip through pages written 100 years ago and summon an image of this letter, or any other entry. If needed, Gonne’s handwriting can be deciphered on a pop-up screen that types out her fevered scrawl.

The notebook is one of thousands of elements in a dazzling exhibition, “The Life and Works of William Butler Yeats,” more like a life-size, walk-through Web site than an ordinary museum show. With audiotapes, four short films and software that brings light and breath to aging manuscripts, it amounts to a digital resurrection, allowing Yeats to stride again along the hinge of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The exhibition, which opened in 2006 and will run until January, then move to the United States if the library can find a suitable host, was mounted in part as a gesture of gratitude to the Yeats family. Soon after the poet’s death in 1939, his widow, George, began giving his papers to the National Library. Those gifts continued from his daughter, Anne, an artist and stage designer who died in 2001, and from his son, Michael, an Irish senator who died in 2007.

The papers now occupy 38 yards of shelves; his personal library of 3,000 volumes has its own space. Catherine Fahy, one of the curators, said the family believed his papers belong to Ireland. “There was also the practical problem of scholars coming to George Yeats for access to them,” she added. And thanks to various loans, paintings by Yeats (he was briefly an art student) and by his accomplished father, John Butler Yeats, and brother, Jack B. Yeats, are put to excellent use.

The exhibition draws its power not only from nimble navigational tools but also from the intimacy of the encounters. The four films are shown in cozy rooms that can seat only five or six at a time, in spaces decked out like his study, a backstage corner of the Abbey Theater and Thoor Ballylee, the chronically damp tower in County Galway where Yeats tried to set up home. The first stop is at a chapel-size octagon of screens. The bustle of the Dublin streets falls away, replaced by recordings of a dozen famous poems.

All his verse was meant to be heard, not read. Yeats once said, ‘“Write for the ear, I thought, so that you may be instantly understood as when an actor or folk singer stands before an audience.”

Here the words roll across one screen, while evocative pictures fill the others. The opening of each poem commands silence:

When you are old and gray and full of sleep

And nodding by the fire, take down this book.

When you are old and gray and full of sleep

And nodding by the fire, take down this book.

The readers include Seamus Heaney, Sinead O’Connor and Theo Dorgan, but it is the voice of Yeats himself, reciting “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” at a sing-song pace, that comes as a revelation. Yeats “had a very distinctive Irish country accent, from Sligo,” noted Patrick McAfee, a visitor earlier this month. “That was amazing. And the way he was reciting was very peculiar. My friend said it was rather beelike, like a bee in a glade.”

In the four films Yeats (1865-1939) is presented as public man, poet, lover and occultist, a figure of towering achievement, eccentricities and pretensions. Less than 50 years after famine had decimated the island, and as tensions with England persisted, he championed a distinctly Irish cultural identity. He collected folklore, helped start the Abbey Theater and promoted John Millington Synge, Sean O’Casey and others. On being awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1923, he said he regarded it as “part of Europe’s welcome to the Free State.”

As a member of the Irish Senate he spoke against a law underwritten by the Catholic hierarchy that banned divorce, and recalled that some of Ireland’s greatest figures had been Protestant. His instinct, Seamus Heaney says in one film, was to find and stand by underdogs as power in society shifted. He also found his way into a eugenics society in 1936, and before then dabbled with the fascist Blueshirt movement. “A flirtation,” Mr. Heaney says, “but not an affiliation.”

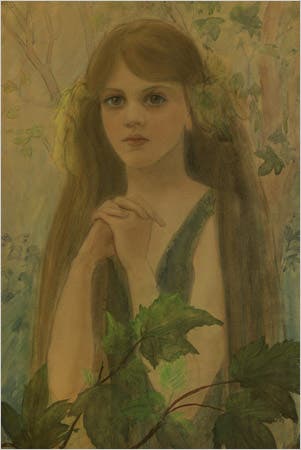

A pastel portrait by Maud of her daughter, Iseult. Yeats had, at various times, asked both women to marry him.

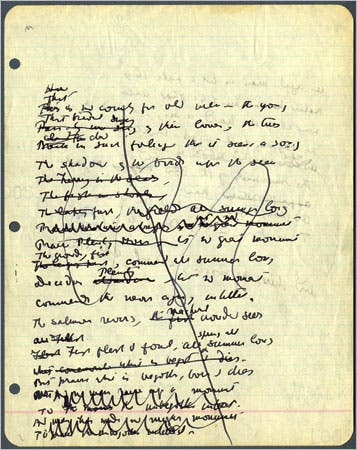

At its core the exhibition offers Yeats’s papers not as relics but as living documents.

The visitor sees a manuscript of “Sailing to Byzantium.” Next to the display a digital tutorial shows how he kneaded the words and notions of the poem. Only in later drafts did he find a streak of lightning to open the poem:

“That is no country for old men.”

Elsewhere software developed by the British Library allows visitors to page through digitized manuscripts. For Henry Kerr, a visitor who had chanced into the exhibition, the technology gave him handholds into Yeats’s work. “It works very well, the touch screen and flipping through books, zooming in,” Mr. Kerr said. “It opens it up a wee bit.”

And there is eloquence too in the older media, in the static dignity of oil paintings, or even in an understated line or two on a display card. These elements are especially helpful in tracing the poet’s elaborate romantic entanglements. “I don’t know how he could have done all of it and wrote so much at the same time,” said Sharon Callaghan, a visitor.

How Yeats was inspired to write his poem. Video is from the exhibit at the National Library of Ireland. (Produced by Martello Media)

At their center was Maud Gonne, whom Yeats met in 1889, when, as he wrote, “the troubling of my life began.” With her in mind for the lead role, he composed a play, “The Countess Kathleen.” It took him 10 years. “The play was performed at the opening of the Irish Literary Theatre in 1899,” the exhibition notes. “Maud Gonne refused to take part in it.”

Unknown to Yeats, Gonne had an affair with a French journalist and secretly gave birth to a boy, who died at the age of 2; she returned with her lover to the child’s tomb to conceive again, believing that reincarnation would bring back the lost son.

The ordinary brushstrokes of life glow in their links to Yeats’s art. She kissed him on the lips for the first time in 1899, then immediately confessed the truth about the affair and the children she had told the world were adopted. Their friendship survived her regular refusals to marry him, but he was devastated after she took another nationalist, Major John MacBride, for her husband. When that marriage went bad, Yeats comforted her. They apparently were physically intimate near the end of 1908, but she ended it a few months later.

In 1916, at 51 and still a bachelor, he consulted an astrologist, then turned again to Gonne with an offer of marriage. She declined. With her permission he proposed to her 22-year-old daughter, Iseult, who had been conceived at her brother’s grave. She too said no.

Besides being barking mad, everyone in this circle, it seems, could paint. “She is just fabulous looking,” Ms. Callaghan said, gazing at a portrait of Iseult by Maud.

Yeats eventually married Georgina Hyde Lees (he called her George) in 1917, when she was 25 and he was 52. They had two children. At last, his Maud obsession seemed to ebb, nearly 30 years after they first met. His love life remained a tangle. Late in life he had a vasectomy, believed at the time to improve men’s potency. He charged ahead with a dizzying series of affairs, and on his death in January 1939, both his wife and his last lover stood vigil at his bed.

Until nearly the end of his days he and Gonne kept an eye on each other. In 1938 he wrote “A Bronze Head” about her frequent appearances at political funerals, a “dark tomb-haunter,” so transformed from the light, gentle woman of his memory.

Almost from the beginning she had been a figure of memory. In the opening pages of the 1908 notebook he looked backward: “She said something that blotted away the recent past & brought all back to the spiritual marriage of 1898. She believed that this bond is to be recreated & to be the means of spiritual illumination between us. It is to be a bond of the spirit only.”

Flipping ahead in the digital pages, one lands on Yeats’s July 26 entry and learns that he too had relished the astral meeting that Gonne would chronicle so ecstatically. “Noticed also that for the first time for weeks,” he wrote, “physical desire was awakened.”

When her letter arrived, he would learn they were not quite synchronized. “Material union is but a pale shadow compared to it,” she wrote. “Write to me quickly & tell me if you know anything of this.”

Yeats knew it well.

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/20/arts/design/20dwye.html

Untitled

Untitled